Writing an audio guide script is not the same as writing a museum label. Labels sit on a wall. Audio occupies a visitor's ears while they stand in front of something real, in a room full of other people, probably a little tired. That context changes everything about how you should write.

For decades, the process looked roughly the same: a curator drafts text, an editor reshapes it for the ear, a voice actor records it, and the museum ships it. That process works. It also costs a fortune, takes months, and produces something frozen. A fixed recording that can't adapt to who's listening or what they care about.

AI is changing the job. Not replacing it. But the skill is shifting from "write a script" to "direct a guide."

The traditional approach still has lessons

The fundamentals of good audio guide writing haven't changed, and they're worth knowing even if you never write a word-for-word script again.

150 words per minute. That's the comfortable pace for spoken English. Most stops should land between 60 and 90 seconds, which means 100 to 135 words. Go longer and you lose people. We've watched visitors pull out earbuds at the two-minute mark consistently, across dozens of sites.

Write for the ear, not the page. Museum labels and catalog entries are written to be read. Audio guide scripts must be written to be heard. Shorter sentences, simpler syntax, and an assumption that the listener can't re-read a phrase they missed. If you'd put a semicolon in the sentence, it's too complex for audio.

Conversational, not academic. The best traditional scripts read like a knowledgeable friend talking, someone who knows the material deeply but isn't performing their expertise. "This painting was completed in 1889, just a year before van Gogh's death" beats "Completed in 1889, this work represents a late-period example of the artist's post-Impressionist output."

Context before detail. Tell the visitor what they're looking at and why it matters before you get into dates, techniques, or provenance. If someone doesn't know why they should care within the first ten seconds, you've already lost them. Orientation first, depth second.

These principles cost real teams real money to learn. Don't throw them away just because the production method is changing.

Why traditional scripts are expensive and brittle

A single professionally produced audio guide stop (script, review, recording, editing) can run $500 to $1,500. Multiply by 30 stops and you're looking at $15,000 to $45,000 for one language. Now do that in five languages. Then the permanent collection rotates a few pieces and you need to re-record.

The economics create bad incentives. Museums under-invest in the script because the production budget is already stretched. They cover fewer stops because each one is expensive. They skip languages because translation and re-recording doubles or triples the cost. And once it ships, nobody wants to touch it. Updating means going back through the entire production pipeline.

The result: most audio guides cover a fraction of what a museum actually has, in a fraction of the languages visitors speak, and they stay static for years after the content around them has changed.

There's a deeper problem too. A traditional script is a monologue. It can't respond to what a visitor is interested in, adjust if they seem confused, or skip ahead if they already know the background. Every visitor gets the same 90 seconds regardless of whether they're an art history professor or a teenager on a school trip.

The shift: from scriptwriter to director

AI-generated audio guides don't use scripts. They generate speech in real time, responding to the visitor's position, questions, and behavior. So the museum professional's job isn't to write what the guide says word-for-word. It's to shape how the guide thinks, what it knows, and what it should emphasize.

Think of it like the difference between writing a screenplay and directing an actor who improvises. You're not scripting lines. You're setting the character's knowledge, personality, boundaries, and priorities, then letting it perform within those constraints.

This is a real skill, and it's different from traditional scriptwriting. Some of what transfers: you still need to understand pacing, tone, and what makes audio engaging. What doesn't transfer: the line-by-line wordsmithing. You're working at a higher level of abstraction.

How layered prompting works in practice

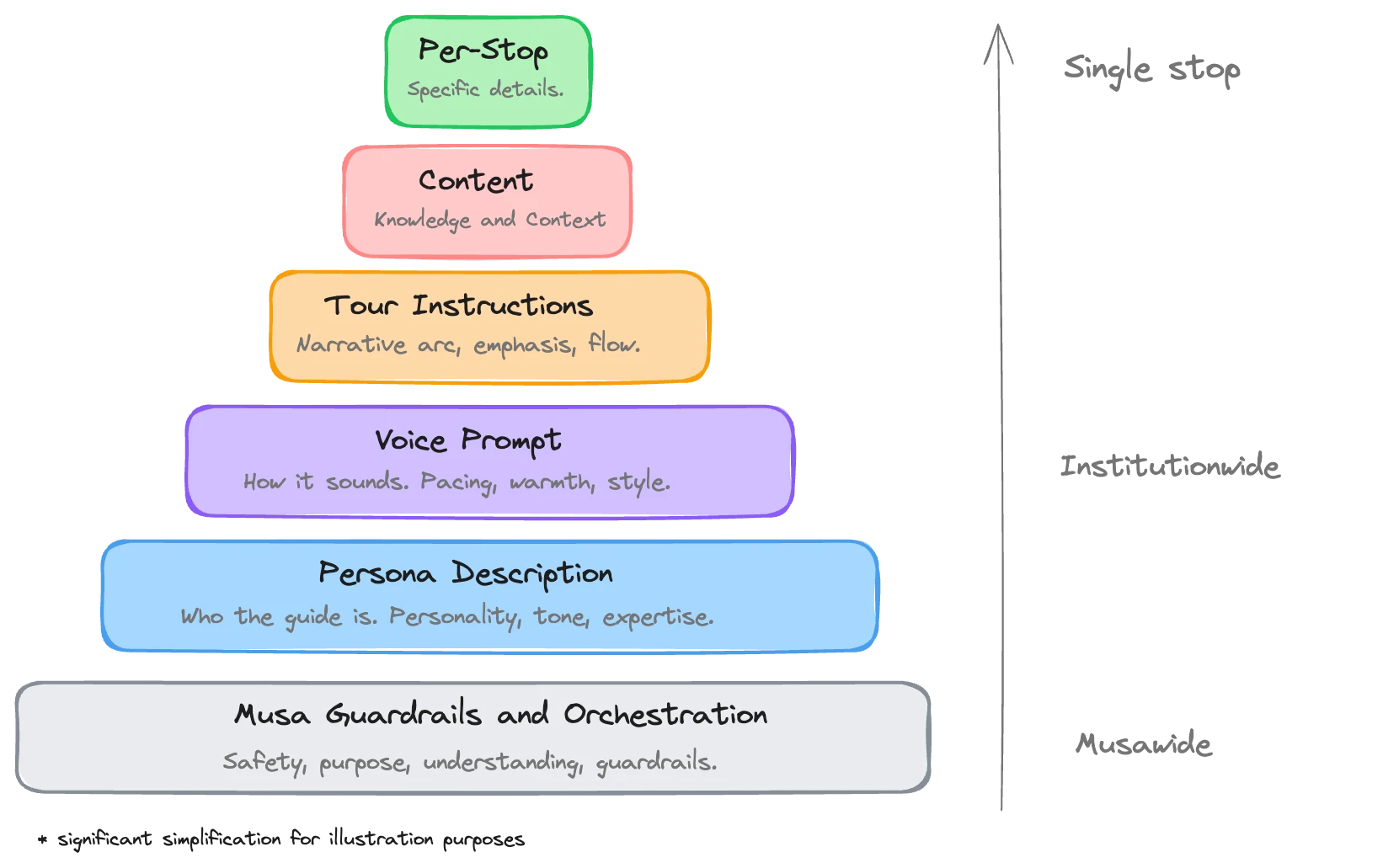

At Musa, we've built a system where museums control their guide's behavior at four distinct layers. Each one does something different, and understanding the separation is what makes the difference between a generic AI response and something that actually sounds like your institution.

Persona description. This is the guide's character: their personality, tone, depth of expertise, and approach to visitors. An art historian character will speak differently than a kids' guide or a local storyteller. The persona description defines who the guide is, independent of any specific tour or stop. You might write something like: "You are a warm, slightly irreverent architectural historian. You love material details, how things were built, what went wrong, what the builders argued about. You speak casually but precisely."

Voice prompt. This controls the literal voice: pacing, emotional register, speaking style. It's the difference between a voice that sounds like a radio presenter and one that sounds like someone leaning in to share something privately. Voice prompts work at the speech synthesis level, shaping how words are delivered rather than which words are chosen.

Tour-level instructions. These shape how a specific tour is conducted: the narrative arc, thematic emphasis, what to highlight or skip, how to handle transitions between stops. A highlights tour and a deep-dive tour of the same collection will have different tour-level instructions even if they use the same persona. This is where you control pacing and story structure.

Per-stop instructions. These are specific to individual stops within a tour. You might tell the guide to always mention the restoration controversy at stop 7, or to ask visitors what they notice about the light in a particular painting before explaining the technique. Per-stop instructions let you inject curatorial specificity without scripting every word.

The power is in how these layers compose. The persona stays consistent across every stop. The tour instructions keep the narrative arc coherent. The per-stop instructions handle the details. None of it requires writing out exactly what the guide will say.

What this means for your workflow

Once you've designed the scaffolding (persona, voice, tour structure, per-stop notes) adding content becomes almost trivial. A new acquisition goes into the collection data. You add the stop to the relevant tours. Maybe you write two sentences of per-stop context. The guide already knows how to speak, what tone to use, and how to fit the new piece into the broader narrative.

Compare that to traditional production: draft a script, get curatorial review, rewrite, record, edit, localize, distribute. For one stop.

The 80/20 principle applies strongly here. You get very high quality results from the basic setup: loading your data, choosing a persona, and ordering your stops. The optional layer of per-stop instructions and detailed tour prompts takes it from good to precisely calibrated. But even without that extra work, the guide speaks in your voice because the persona and knowledge base are yours.

In our experience, a complete museum onboarding (data ingestion, tour design, persona creation, testing) takes less than a week. That's from "we've never used the platform" to "visitors are taking guided tours." Compare that to the months-long timeline of traditional production.

You still need curatorial judgment

None of this means the museum's role shrinks. If anything, it gets more interesting. Instead of laboring over whether "completed" or "finished" is the right word in stop 14, you're making higher-order decisions. What kind of character should guide visitors through a sensitive historical exhibition? How should the guide handle questions that go beyond the collection data? What's the right balance between storytelling and factual depth for your audience?

These are curatorial decisions. They require domain expertise, institutional knowledge, and taste. AI handles the generation. Humans handle the direction.

One thing we tell museums: think less about audio guides and more about tour guides. Imagine a person with deep knowledge of your collection who follows your guidance, speaks the way you want, and adapts to every visitor. That mental model, directing a knowledgeable person rather than writing a recording, is the shift that makes AI-powered guides click.

Practical tips for writing AI guide instructions

If you're designing prompts and personas rather than traditional scripts, here are things we've learned work well:

- Be specific about what not to do. "Don't mention auction prices" or "Don't speculate about the artist's personal life unless the visitor asks." Negative instructions are often more useful than positive ones.

- Give the persona opinions. A guide that says "this is one of the most underrated pieces in our collection" is more engaging than one that presents everything with equal weight. Museums curate. Your AI guide should too.

- Write per-stop instructions for your strongest stops. You don't need them everywhere. Focus on the stops where you have a specific story to tell or a particular angle you don't want the AI to miss.

- Test with real questions. The best way to evaluate your setup isn't reading transcripts. Stand in front of the actual artwork and ask the guide questions a visitor would ask. "What's happening in this painting?" or "Why is this one famous?"

- Iterate on the persona, not individual responses. If the guide sounds too academic, don't fix it stop by stop. Adjust the persona description. Changes propagate everywhere.

Getting started

If you're currently writing traditional audio guide scripts, the transition isn't a cliff. It's a gradient. The instincts you've developed about pacing, tone, and what makes audio engaging are exactly what you need. The craft shifts from writing to directing, from word-level control to system-level design.

If you're thinking about this for your own institution, get in touch and we'll show you how it works in practice. The best way to understand the difference is to hear it.