Every museum audio guide needs to answer one question: how does the visitor's phone know which exhibit they're standing in front of?

The technology industry has offered several answers over the past decade. Bluetooth beacons. NFC tags. QR codes. GPS. Each promises to solve the positioning problem. Each comes with trade-offs that vendors tend to understate in their sales decks.

We've spent a lot of time thinking about this at Musa, because positioning is the foundation that the rest of the audio guide experience sits on. Get it wrong and everything built on top — the narration, the navigation, the suggestions — falls apart. Get it right and visitors forget the technology exists, which is exactly the point.

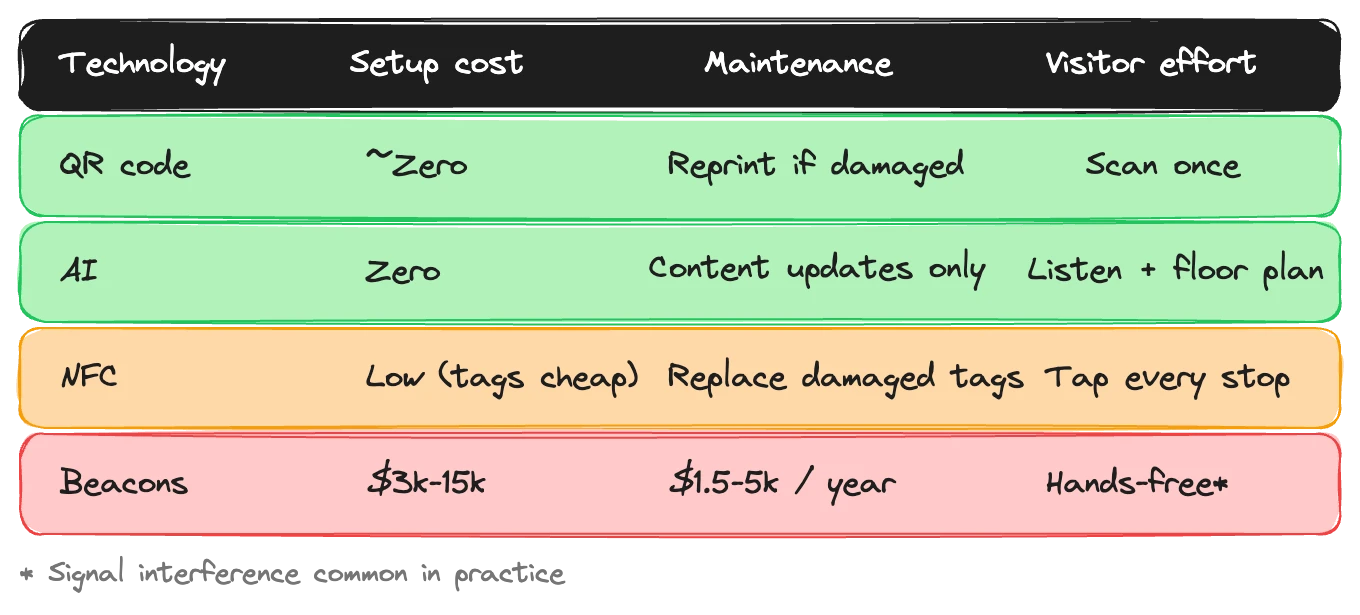

Here's an honest breakdown of what each technology actually delivers in a museum environment.

Bluetooth beacons: the promise vs. the reality

Beacons were supposed to be the future of indoor positioning. The pitch is appealing: install small Bluetooth transmitters near each exhibit, and when a visitor's phone comes within range, the guide automatically triggers the right content. No scanning, no tapping, no effort from the visitor. They just walk, and the guide follows.

In a demo, this looks great.

In a real museum, it's a different story. Beacons run on batteries — typically coin cells that last six to eighteen months depending on broadcast frequency and signal strength. A museum with 60 stops needs 60 beacons, each on its own battery schedule. That's not a one-time installation. It's a permanent maintenance commitment. Someone has to track which batteries are low, swap them before they die, and verify the replacement is working correctly.

Then there's the environment. Museums are full of materials that interfere with Bluetooth signals. Metal display cases. Glass partitions. Thick stone walls in historic buildings. Large crowds absorb and scatter signals in unpredictable ways. A beacon that triggers perfectly during a Tuesday morning walkthrough might misfire on a Saturday afternoon when the gallery is packed. We've heard from museums where visitors standing between two exhibits would get content for the wrong one, or for both at once.

Calibration is ongoing, not one-time. Move a display case and your signal profiles change. Rearrange a gallery for a temporary exhibition and you may need to recalibrate every beacon in the room. Some museums report spending two to three full days recalibrating after any significant layout change.

The cost profile reflects this. Initial installation runs 3,000-15,000 depending on site size and beacon quality. Annual maintenance — batteries, recalibration, replacements for failed units — adds 1,500-5,000 per year. Over five years, the beacon infrastructure alone can cost 10,000-40,000, and that's before you've paid for any content.

None of this means beacons are useless. For certain high-budget, stable-layout institutions that can dedicate staff to maintenance, they work. But the gap between the marketing pitch and the operational reality is wider than most vendors acknowledge.

NFC: precise but limiting

Near-field communication takes the opposite approach from beacons. Instead of broadcasting to everything within range, NFC requires the visitor to bring their phone within about four centimetres of a tag. Tap the phone against a small tag mounted near the exhibit, and the guide loads.

The precision is a real advantage. There's zero ambiguity about which exhibit the visitor wants — they physically tapped it. No interference, no signal bleed between adjacent displays, no calibration. The tags are cheap (pennies each), passive (no batteries), and durable.

The limitation is equally obvious. Four centimetres is close. The visitor has to know the tag exists, find it, and hold their phone against it. For a single high-value interaction — unlocking a special piece of content at a flagship exhibit, say — this is fine. As a navigation method for an entire tour, it's tedious. It's the same problem as QR-code-at-every-stop, except the visitor has to get even closer.

NFC also requires the museum to mount tags at every stop and replace them if they're damaged or removed. The tags themselves cost almost nothing. The mounting, labeling, and maintenance across a full site is real work.

There's a practical ceiling on NFC. It works as a supplement — a way to trigger a specific interaction at a specific moment. As the primary positioning technology for a full audio guide tour, it asks too much of the visitor at every stop.

QR codes: boring, reliable, underrated

QR codes get dismissed as low-tech. They are. That's exactly why they work.

Print a code. Stick it near an exhibit. Visitor scans it with their phone camera. Done. No batteries. No Bluetooth. No NFC hardware. No calibration. No interference from materials or crowds. No ongoing maintenance cost beyond occasionally reprinting a code that's been damaged.

The production cost is essentially zero. You can generate QR codes for free and print them on any surface — a label, a panel, a stand, a wall mount. If a code gets dirty or torn, you print another one. If you rearrange the gallery, you move the printout. The whole thing is almost comically simple compared to a beacon deployment.

The weakness is that QR codes require the visitor to do something. They have to pull out their phone, open the camera, aim it at the code, and wait for the content to load. This is a real friction point. Each scan is a small interruption to the visitor's experience. For a tour with 30 stops, that's 30 interruptions. Studies on museum audio guide behavior consistently show that scan-per-stop engagement drops off sharply after the first few stops. Visitors get tired of the repetition and start skipping.

So QR codes are the most reliable, cheapest, and lowest-maintenance positioning technology — but only if you use them wisely.

The scan-once model

Here's where the approaches diverge most sharply: how many times does the visitor have to interact with the positioning technology?

Beacon advocates argue: zero times. The visitor just walks and the guide follows. In theory, yes. In practice, misfires and interference mean the visitor is often tapping to correct the system, which means the hands-free promise doesn't fully deliver.

The QR-at-every-stop model requires an interaction at every single exhibit. Thirty stops, thirty scans. This is the default for most budget implementations, and it's why many museums report poor completion rates on their audio guides.

The model we've landed on at Musa is scan-once. A visitor scans a single QR code to enter the tour — at the front desk, on a banner, wherever makes sense. After that, the app handles everything. No more scanning. The visitor navigates through the tour using the app interface. The guide knows the tour path, shows what's coming next, offers suggestions for nearby exhibits, and lets visitors diverge from the curated route whenever they want.

If someone wants to jump to a specific exhibit out of order, they type its name. This sounds almost too simple, but it's fast and works regardless of where the visitor is standing. No need to find a QR code, no need to be within NFC range, no need to wait for a beacon to pick them up. Just type "Blue Period Room" or "Egyptian Gallery" and go.

One scan to enter. Then the guide runs the show. The technology gets out of the way and the content takes over.

Indoor positioning without hardware

The scan-once model still needs to answer the positioning question. If the visitor isn't scanning at each stop and there are no beacons, how does the system know where they are?

Musa handles this with two tools that require zero installed hardware.

Visual anchor points are reference images of specific locations within the museum — a distinctive doorway, a room's corner view, a prominent display. Visitors match what they see on screen to what they see in front of them. It sounds manual, but in practice it's quick and intuitive. "You should see the large bronze horse to your right" is a more natural wayfinding prompt than a blinking beacon icon on a map.

Floor plans give visitors spatial context. The tour shows where they are relative to the overall layout, where the next stop is, and how to get there. Combined with visual anchors, this gives visitors enough positioning information to follow a curated tour without any scanning or hardware assistance after that initial QR code.

For outdoor sites, GPS replaces floor plans. Phone GPS is accurate enough to track visitors across an open heritage site and trigger content at the right points of interest. Indoor, GPS fails — the satellite signal degrades inside buildings. But visual anchors and floor plans take over wherever GPS drops out.

This is Musa's primary differentiator on the positioning question. No beacons to install, maintain, or troubleshoot. No tags to mount at every stop. The positioning layer is entirely software — content and interface, not hardware.

The infrastructure question

When a museum evaluates positioning technology, the conversation usually focuses on accuracy and visitor experience. Those matter. But there's a question that matters more in the long run: what are you committing to maintain?

Beacons are infrastructure. They need batteries, calibration, monitoring, and eventual replacement. They tie you to a specific vendor's hardware ecosystem. If the beacon manufacturer discontinues the product line — which has happened multiple times in the past five years — you're looking at a full replacement, not a firmware update.

NFC tags are simpler infrastructure but still physical. They need mounting, they can be damaged, and any layout change means moving and potentially replacing tags.

QR codes are disposable infrastructure. Print them, stick them up, reprint when needed. The total ongoing cost rounds to zero.

Software-based positioning — visual anchors, floor plans, GPS — isn't infrastructure at all. It's content. It lives in the CMS alongside the tour narration and exhibit descriptions. Update it the same way you'd update any other content. No site visit required, no technician, no tools.

The question isn't just "which technology is most accurate today?" It's "which technology will still be working properly in three years without dedicated maintenance staff?"

When beacons might still make sense

We're not arguing that beacons are always wrong. There are scenarios where they earn their keep.

High-traffic institutions with dedicated technical staff. A major national museum with an in-house IT team and a six-figure technology budget can absorb the maintenance overhead. For these institutions, the hands-free visitor experience may be worth the operational cost.

Specific trigger points, not full tours. Using a few beacons at key locations — the entrance, a star exhibit, the exit — rather than blanketing the entire site. Five beacons are manageable. Sixty are a headache.

Environments with minimal interference. Open-plan, modern gallery spaces with few metal obstacles and consistent traffic patterns give beacons the best chance of performing reliably.

Outside these cases, the cost-to-benefit ratio tilts against beacons for most museums. And the trend line is clear: the industry is moving toward software-based positioning precisely because it removes the hardware dependency that creates ongoing cost and risk.

Where this is heading

The broader shift in museum technology is away from installed hardware and toward phone-native, software-driven systems. Beacons were a reasonable bet a decade ago, when phones had limited capabilities and cloud infrastructure was expensive. Today, the phone in a visitor's pocket has more processing power, better sensors, and more connectivity options than any beacon network can match.

Visual positioning — using camera-based recognition to identify location — is where things are heading next. It's already used in AR applications and large-venue navigation. As phone cameras and on-device processing improve, the accuracy gap between visual positioning and beacon-based systems will continue to close, and visual positioning carries none of the maintenance burden.

Musa's current approach of visual anchor points is a practical, today-ready version of this trajectory. It doesn't require sophisticated computer vision on the visitor's device. It uses human pattern matching — "do you see this?" — which works on any phone, in any connectivity condition, with no special hardware. As the technology matures, more automated visual positioning will layer on top of this foundation without requiring museums to install anything new.

The museums that invest in content rather than infrastructure will have the most flexibility as these technologies develop. Your narration, your curatorial voice, your exhibit data — that transfers to any delivery system. A beacon network does not.

Choosing for your museum

The practical decision framework is simpler than the technology comparison suggests.

If you have technical staff, a stable layout, and budget for ongoing maintenance, beacons can deliver a polished hands-free experience. Budget for the true five-year cost, not just the installation quote.

If you want the cheapest reliable option with zero ongoing cost, QR codes work. But use the scan-once model, not scan-per-stop. One QR code at the entrance, then software handles the rest.

If you want to avoid hardware infrastructure entirely, software-based positioning with visual anchors and floor plans is the approach we'd recommend — and it's what we've built Musa around.

Whatever you choose, don't let the positioning technology become the thing visitors notice. The best wayfinding is the kind nobody thinks about. The guide just knows where you are, the right content plays, and the visitor's attention stays on the art, the artifact, the story.

If you're evaluating positioning options for an audio guide and want to talk through what fits your space, reach out.