Most audio guides are designed around a floor plan and an assumption: visitors will start at stop one and proceed in order to stop twenty. The guide is scripted for that sequence. The floor plan has a suggested route. A little arrow says "start here."

Then visitors walk in and do whatever they want.

They turn right instead of left. They skip the first three rooms because the temporary exhibition caught their eye. They spend twenty minutes with one painting and walk past the next six. Two people enter the same museum and take completely different paths through identical galleries.

This is the reality to design for.

The consultant model

The traditional approach to understanding visitor flow is to hire a consultant, run a time-and-motion study, and produce a report. Staff members stand in galleries with clipboards and tally sheets, recording which way visitors turn at each intersection, how long they stand at each display, and where they get confused.

This data gets turned into a single "optimal path," the route that the most visitors naturally follow, smoothed into a recommended sequence. The audio guide gets built around that path. Done.

The problem is that this path describes an average that doesn't represent anyone in particular. It's a statistical composite. The actual visitors — the ones who came specifically for the ceramics, or the ones with a stroller who skip the stairs, or the school group that starts in the back — none of them walk the optimal path. You've designed an experience for a visitor who doesn't exist.

The study also captures a snapshot. Visitor flow changes by day of week, by season, by what's in the temporary exhibition hall. A study conducted in March may not describe what happens in August. And unless you plan to pay for another study, you'll never know.

What data actually shows

When you stop trying to define the optimal path and instead look at how visitors actually move, patterns emerge that are more useful than any single recommended route.

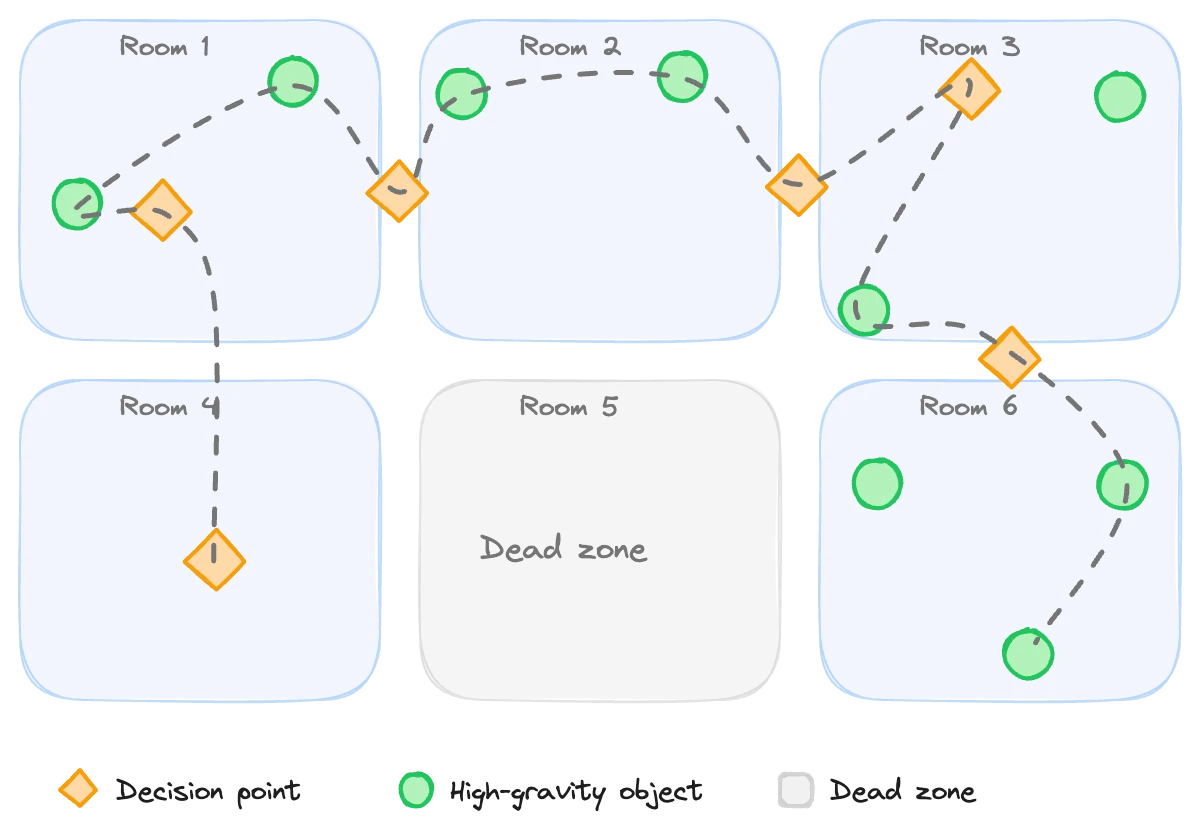

You'll find that your space has a small number of decision points: locations where visitors orient themselves and choose a direction. A doorway between two galleries. A landing where three corridors meet. The center of a large open room. These aren't stops on a tour. They're moments of navigation where the visitor's experience could branch.

In a typical medium-sized museum, there might be eight to twelve of these decision points. Most visitors will pass through most of them, but in different orders and from different directions. The decision points are the skeleton of your space. Everything else is what happens between them.

You'll also find clusters. Certain objects attract disproportionate attention regardless of where they sit. People photograph them, stand in front of them longer, point them out to companions. These high-gravity objects are natural anchor points for any tour. Not because a curator decided they're important (though they often are), but because visitors independently gravitate to them.

And you'll find dead zones. Corners that most people walk past. Rooms that feel like detours. Displays that sit between two high-traffic areas and get nothing. Knowing where these are tells you where an audio guide can make the biggest difference. Not by forcing visitors into those spaces, but by giving them a reason to go there.

Mapping your decision points

You don't need a consultant for this. You need a few hours of observation and a floor plan.

Walk your space from the entrance. Every time you reach a point where the path isn't obvious — where a visitor would need to decide which way to go — mark it. Not every doorway qualifies. A narrow corridor with one way forward isn't a decision point. A gallery that opens into two adjoining rooms is.

At each decision point, note what's visible from that spot. Can visitors see what's in the next room? Is there signage? Is the lighting different in one direction? These environmental cues influence which way people turn, often more than any map or recommendation.

Then watch. Spend thirty minutes at each decision point during a busy period. Don't count every visitor, just note the ratio. Do most people go left or right? Do they pause and look around, or do they walk through without hesitating? A decision point where everyone pauses is a point of confusion. A decision point where everyone turns the same way is a natural flow. Both are useful information for different reasons.

The result is a map of how your space actually functions, not how the architect intended it or how the floor plan suggests it should work.

From one path to many experiences

Traditional audio guides need a single path because producing content for multiple paths is prohibitively expensive. Every additional route means more scripts, more recordings, more production time. So you pick one and hope it works for most people.

When content generation isn't bottlenecked by production cost, you can design for how visitors actually behave. Instead of one optimal path, you can create multiple overlapping experiences that share the same underlying knowledge but present it differently.

A highlights tour that hits ten objects in forty minutes. A thematic tour focused on a specific period or medium. A deep-dive tour for repeat visitors who've already done the basics. A children's tour that follows a different route entirely because it skips the rooms with fragile displays and detour-prone layouts.

None of these tours needs its own production run. They're different configurations of the same knowledge, delivered by the same system. The decision of which tour to offer which visitor becomes a design choice, not a budget constraint.

We see this during onboarding with Musa. A partner site focused on Gaudi's work realized they could offer a dedicated ceramics tour, something they'd never have commissioned separately because the production cost for a niche tour couldn't be justified. With AI generation, the cost of creating that tour was effectively zero. The content already existed in their knowledge base. They just needed to curate the sequence.

How spatial processing works in practice

Mapping visitor journeys through your space used to require floor plans, architectural drawings, or expensive surveys. Many museums, especially heritage sites and historic houses, don't have accurate digital floor plans at all.

At Musa, we handle this during onboarding. We ask partners for a walkthrough video of their space — someone walking through the galleries with a phone camera, covering the visitor-accessible areas. That video goes through a spatial processing pipeline that analyzes the footage and identifies navigation points, spatial relationships between rooms and objects, sight lines, and architectural features that affect visitor flow. The output helps us create floor plans and configure the tour's spatial logic.

The museum doesn't do this part. The Musa team handles the spatial analysis, the data ingestion, and the initial tour setup. If the museum has an existing audio guide, we take that too: replicate the current experience first, then layer AI capabilities on top. The onboarding approach is: give us what you have, we'll build from there.

That removes the main barrier. You don't need to commission floor plans or hire a spatial consultant. You need a phone and twenty minutes to record a walkthrough.

Museum control, visitor flexibility

There's a tension in audio guide design between curation and freedom. Museums have stories to tell: narrative arcs that build across rooms, thematic connections that only land if you encounter things in a certain order. But visitors want to wander. They want to follow their interest, double back, skip ahead.

Bad audio guides resolve this tension by ignoring one side. Either the guide is rigidly sequential (and breaks the moment someone goes off-path) or it's a disconnected set of standalone commentaries (and there's no narrative at all).

The better answer is a system where the tour order stays museum-curated but the visitor can diverge without the experience falling apart. The museum defines the sequence — this room, then that room, building toward a particular conclusion. But if a visitor skips room three and goes straight to room five, the guide picks up at room five and adjusts. The story continues. It might reference what the visitor missed or weave it in later if they circle back. The narrative thread holds.

Musa works this way. The museum designs the tour structure: the sequence, the emphasis, the narrative arc. That curation stays intact. But the AI adapts delivery based on where the visitor actually is and what they've actually encountered. If a visitor asks a question that pulls the conversation in a different direction, the guide follows that thread and then returns to the curated path.

The museum stays in control of the story. The visitor stays in control of their movement. Both get what they need.

The Q&A layer

Journey mapping changes when the guide can respond to questions. In a traditional audio guide, the journey is strictly spatial: the visitor walks, the guide narrates. The visitor's only input is their position.

With conversational AI, the visitor's questions become part of the journey. Someone standing in front of a Renaissance portrait might ask about the artist's technique, or the historical context, or why the painting is displayed next to this particular sculpture. Each question sends the experience in a slightly different direction while the visitor stands in the same spot.

So the "journey" stops being purely spatial. Two visitors can take identical physical routes through the museum and have entirely different experiences because one asked questions and the other just listened.

For journey mapping, your tour design needs to account for depth, not just sequence. At each stop, what are the likely questions? What rabbit holes might a visitor go down? The curated narration handles the surface layer. The Q&A layer handles everything beneath it, and the depth is limited only by the knowledge in your system.

Practical steps for your museum

If you want to start thinking about visitor journeys more deliberately, here's a concrete approach.

-

Walk your space as a first-time visitor. Enter through the public entrance. Don't use staff shortcuts. Note every moment you have to decide which way to go. These are your decision points.

-

Observe for a day. Station someone (or yourself) at each decision point for thirty minutes during a peak period. Note the split: what percentage goes which direction. Note the hesitation. Are people pausing, looking at maps, looking lost?

-

Identify your high-gravity objects. Which displays consistently draw crowds? Where do visitors take photos? Where do they call companions over? These are your anchor points regardless of what tour you design.

-

Find the dead zones. Where do visitors thin out? Where does foot traffic drop? These are either rooms to rethink or opportunities for an audio guide to add a reason to visit.

-

Sketch three different tours. Not one. Three. A short highlights tour, a thematic tour focused on whatever your strongest collection area is, and a full-length tour. See how they overlap at your decision points.

You're not aiming for a perfect map. You're trying to understand your space as a network of possibilities, then design audio experiences that work with that network rather than against it.

Getting started

Journey mapping sounds academic, but the practical version is straightforward. Walk the space. Watch the visitors. Note where they choose, where they linger, where they leave. Then design tours that match what you see rather than what you assume.

If you'd like help with this — or want to see how spatial processing and AI-guided tours work with your specific space — we can walk you through it.