The conventional wisdom in the museum technology world is that launching an audio guide takes six months to a year. You draft an RFP. You evaluate vendors. You commission scripts. You hire voice actors. You record, edit, localize, test the hardware, deploy charging stations, train front desk staff. Somewhere around month nine, visitors get to use it.

That timeline made sense when audio guides were hardware products. It doesn't make sense anymore.

We've onboarded museums (entire institutions, not single exhibitions) in under a week. Thousands of items ingested, tours designed, characters built, guides speaking in the museum's voice across dozens of languages. The technology bottleneck is gone. What remains is a question of process: how quickly can you move from "we want an audio guide" to "visitors are using it"?

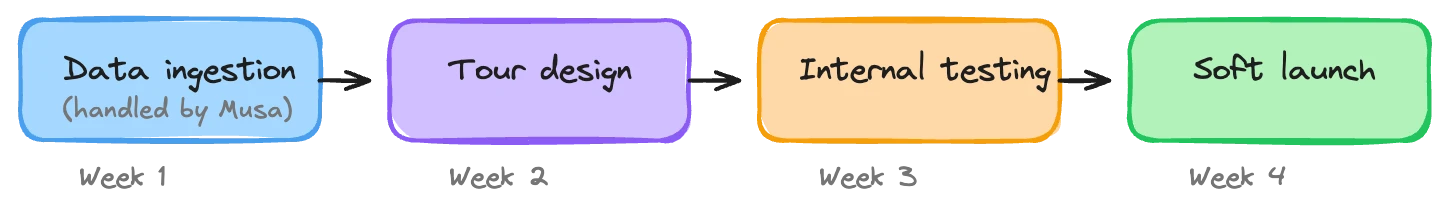

The answer, if you're willing to work iteratively, is about 30 days to a live pilot.

Why the old timeline exists

Traditional audio guide production has a lot of sequential dependencies. You can't record until the script is final. The script can't be final until curatorial review is complete. Curatorial review can't start until someone writes the first draft. Translation can't begin until the source language is locked. Hardware can't be ordered until you know the content length and technical requirements.

Each step waits for the previous one. Each step involves different people, different budgets, different approval chains. A two-week delay at any point cascades through the entire project. That's why "6 to 12 months" is the standard answer: not because the work itself takes that long, but because the process has so many handoffs.

AI-generated guides remove most of these dependencies. There's no script to write per stop. No recording session to schedule. No per-language translation budget to approve. The guide generates speech in real time from your data, shaped by the persona and instructions you define. Months of sequential production collapse into days of parallel setup.

But faster technology doesn't automatically mean faster launches. You still need a plan. Here's one that works.

Week 1: Data ingestion and initial design

This is the heaviest week for the provider. For you, it's mostly about handing over what you already have.

What you provide: Your collection data in whatever format it exists: spreadsheets, a collections management export, catalogue PDFs, wall text documents, existing audio guide scripts. Floor plans or a walkthrough video of your spaces. Any curatorial notes, thematic frameworks, or interpretive priorities you want the guide to reflect.

What happens on the other side: The provider ingests all of this. At Musa, this means loading it into the platform, structuring it into stops, and building out the spatial relationships between objects and galleries. We create initial tour designs, often starting by replicating the museum's existing audio guide tour as a baseline, then layering the AI capabilities on top.

This is also when the guide's character gets built. Voice, tone, personality, behavioral guardrails. If you're a history museum that wants an authoritative but approachable narrator, that gets defined now. If you want a warmer, more conversational persona for a house museum, that's a different set of instructions. The character is what makes the guide sound like your guide, not a generic AI reading facts.

By the end of week one, there's a working prototype. Not polished. Not final. But a tour that a visitor could actually walk through, hearing your content delivered in your voice, with the ability to ask questions and get answers grounded in your data.

"Full onboarding in a week" sounds like marketing language. It's not. The technical work (ingesting data, building tours, configuring characters) is fast when the platform is built for it. We've added thousands of collection items in days. The constraint isn't the technology; it's getting the source material from the museum, which is why we ask for everything upfront.

Week 2: Your team breaks it

Now the museum gets involved. Hand the prototype to your curators, educators, front-of-house staff, and anyone else whose opinion matters. Ask them to use it like a visitor would: walk the tour, ask questions, try to confuse it, see what feels wrong.

This step matters more than most museums expect. The prototype will be surprisingly good in some places and noticeably off in others. Maybe the guide emphasizes provenance when your curatorial philosophy leads with visual analysis. Maybe it doesn't mention the connection between two objects that everyone who works there considers obvious. Maybe the tone is right for the main galleries but too formal for the temporary exhibition space.

These aren't bugs. They're calibration. Every piece of feedback at this stage is easy to act on: a tweak to the character instructions, a per-stop note, an adjustment to the tour order. The changes take minutes, not weeks, because you're editing instructions rather than re-recording audio.

What "ready" looks like at the end of week 2: The guide covers your priority stops. The tone matches your institutional voice. Curators aren't cringing at factual issues. Front-of-house staff can explain to visitors what it is and how to access it. There will still be rough edges. That's fine.

Week 3: Real visitors, small scale

Put the guide in front of actual visitors. Not all of them, just a small group. Maybe you mention it at the front desk to every tenth visitor, or you set up a QR code in one gallery, or you invite your members for a preview.

The goal here is not to validate whether the guide is perfect. It's to learn things that internal testing can't reveal.

Internal testers know your collection. They know the building. They know what the guide is "supposed" to say. Visitors don't have any of that context. They'll ask questions your curators would never think of. They'll skip stops you assumed were essential. They'll spend ten minutes on an object your team barely discussed. They'll try to use the guide in ways you didn't design for.

This is the most valuable data you'll collect in the entire process. With an AI-generated guide, you get the conversational layer: not just "did they listen to stop 7" but "what did they ask about at stop 7, and did they seem satisfied with the answer?"

Keep a short feedback mechanism in place. Even a one-question "How was the audio guide?" at the exit captures signal. But the real insights come from the usage data: which stops get questions, where people drop off, what languages are being used, which tour paths visitors actually follow versus the one you designed.

Week 4: Wider dog-fooding and iteration

Expand the visitor group. Promote the guide more actively: signs at the entrance, mention on your website, staff actively offering it. You're still in preview mode, but the circle is wider.

Simultaneously, incorporate what you learned in week 3. The adjustments at this stage tend to be specific. A stop that confused visitors gets clearer instructions. A section of the tour that people consistently skip gets shortened or repositioned. A question that keeps coming up gets addressed proactively in the narration rather than waiting for someone to ask.

This is where the 80/20 principle earns its keep. Your guide has been good since week one. Weeks two through four are about moving from good to right, making it feel like it belongs in your museum rather than a technology demo. Each round of feedback pushes it closer.

The iteration cycle with an AI guide is fast because changes are live almost immediately. Adjust a per-stop instruction at 10 AM and the next visitor at 10:05 hears the updated version. No rebuild, no redeployment, no waiting for a new binary to roll out to devices. So you can experiment freely. Try a different opening at a popular stop, see if engagement changes, revert if it doesn't work. Traditional guides don't allow this kind of rapid experimentation. Once it's recorded, it's fixed until the next production cycle.

Week 5: Pilot launch

By now, the guide has been tested by your team and used by real visitors. You've iterated on the feedback. The rough edges from week one are gone. You know which stops work well, which need more attention, and what visitors actually care about.

Launch the pilot. Make the guide available to all visitors, promoted properly, with QR codes at the entrance, mentioned on your website, staff trained to explain it.

A pilot isn't a soft launch you hope nobody notices. It's a real launch with the explicit understanding that you're gathering data for a fixed period (typically 30 days) before deciding on a permanent rollout. This framing gives your team psychological permission to ship something that isn't perfect, because the commitment is bounded.

What "pilot" means in practice: The guide is live for all visitors. You're tracking usage metrics: adoption rate, completion rate, language distribution, engagement per stop. You're watching for failure modes: questions the guide handles poorly, navigation confusion, technical issues on certain devices. And you're continuing to refine.

At the end of the pilot period, you have real data. Not projections. Not vendor demos. Actual visitor usage from your museum, with your collection, with your visitors. That data makes the decision about full rollout straightforward.

The pitfalls that slow you down

This timeline is realistic. We've seen museums hit it. We've also seen museums take three times as long, not because the technology was slow but because the process stalled. The same patterns come up repeatedly.

Perfectionism before launch. The single biggest delay. A curator wants every stop to be exactly right before any visitor hears it. The instinct is understandable; you don't want to publish something that isn't up to standard. But an AI guide isn't a printed catalog. It's a living system. Launching with 30 excellent stops and adding more over the next month is better than waiting four months to launch with 200 perfect ones. Visitors don't know what you haven't added yet.

Waiting for all content. Related to perfectionism but distinct. Some museums won't launch until the guide covers every object on display. For a museum with 500 objects, this means weeks of data preparation that delays the entire project. Cover your highlights tour first. Cover the objects visitors actually ask about. Expand from there. The guide doesn't have gaps. It simply doesn't offer commentary on objects that aren't in the system yet. That's the same experience visitors have today without any guide at all.

Trying to cover every edge case. What if a visitor asks about the gift shop? What if they ask in a language we don't officially support? What if they ask something offensive? These are valid concerns, and they all have answers. But solving every hypothetical before launch is a trap. Handle the common cases, launch, and address the edge cases as they appear in real data. Most of the scenarios teams worry about never actually come up.

Too many stakeholders in sequence. If curatorial review leads to education review leads to marketing review leads to director review, each with a two-week turnaround, your 30-day timeline becomes a 90-day timeline before any technology work happens. Run reviews in parallel. Give people a deadline. Accept that not everyone will agree on every detail.

The comparison you should make

When evaluating whether 30 days is fast enough, compare it to the real alternative, not the idealized one.

A traditional hardware audio guide doesn't take 6 months because museums are slow. It takes 6 months because the process requires sequential steps that each take weeks: procurement (4-8 weeks), scripting (6-10 weeks), recording (2-4 weeks), localization per language (3-6 weeks each), hardware deployment (2-4 weeks), staff training (1-2 weeks). And that's if nothing goes wrong, nobody changes their mind, and no loans fall through.

Thirty days from first contact to live pilot, with the option to expand and improve continuously from there, is a different category of project. The work itself is different, not just faster.

After the pilot

The pilot is the starting line, but now you have evidence.

After 30 days of live visitor usage, you know your adoption rate. You know which stops generate the most engagement. You know what languages your visitors actually use. You know where people drop off and what questions they ask. You have data that most museums never get from their traditional audio guides, which only tell you how many devices were rented.

From here, the path branches. Most museums move to a full rollout: wider promotion, integration into the ticketing flow, expansion to cover more of the collection. Some add tours they never would have attempted under the old model: a family tour with a different character, a deep-dive tour for repeat visitors, a tour in a language they'd never have recorded because the audience was too small to justify the cost.

The point is that you're making these decisions from a position of knowledge, not speculation. You've seen what works. You've seen what visitors want. The guide keeps getting better because every week of real usage generates feedback that makes the next week better.

If you've been putting off an audio guide because the traditional timeline felt too long, or because the upfront investment felt too risky, the math has changed. Thirty days is enough to know whether this works for your museum.